Christopher Nolan’s film Inception features a classic optical illusion called the Penrose staircase, which folds back upon itself in space. World-renowned puzzlemaker and LEGO constructor Eric Harshbarger takes us for a walk on the stairs.

“Forever Ascending,” by Eric HarshbargerThe popular film Inception provides its viewers with many twists and turns in both storytelling and visuals. From dreams within dreams and mirror-induced Droste effects to mazes and cityscapes that fold upon themselves, the movie keeps the audience engaged and continuously looking for more. With so much going on (and so much left unanswered), it is understandable that some of the details might slip by the moviegoer.

Still from Inception, courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures

One such detail is an optical illusion that is brought to the screen in the form of an ever-ascending staircase. It is introduced by Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) to Ariadne (Ellen Page) as a way to construct a never-ending dreamscape within an otherwise finite world. The moment plays out quickly, and, as with many of director Christopher Nolan’s scenes, it is assumed that the audience will keep up. If it was not clear what exactly was going on, then allow me to re-introduce you to the notion of the Penrose Staircase.

The illusion takes its name from a father and son duo of mathematicians, Lionel and Roger Penrose, who introduced the impossible object in a 1958 paper. The Staircase cannot be constructed in three dimensional reality due to its property that the steps forever carry the traveler upward in a loop. The same steps are traversed, but, impossibly, after the first time around (or second, or third…) one ends up back at the beginning, and the whole journey starts again. One can turn around on the stairs and descend, as well, with the same effect—continually treading the same ground, over and over.

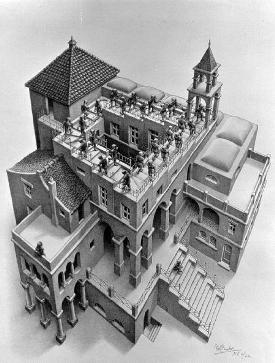

While impossible to build in our real world, that has not stopped mathematicians and artists from depicting the Penrose Staircase as an optical illusion. The most famous example is M. C. Escher’s Ascending and Descending which shows numerous monks laboriously climbing up and down the same steps. By distorting perspective in the two dimensional illustration, the impossibility of the Staircase is removed, and it often takes new viewers a little time to realize that something is not quite right.

The same illusion can be pulled off by cleverly photographing a carefully built sculpture. From most angles such a structure will look like nonsense, but if viewed from just the right position, the faults are hidden and the impossible apparently created.

An extraordinary example of this is provided by Andrew Lipson, a self proclaimed nerd, mathematician, and computer programmer, who, along with Daniel Shiu, built a rendition of Ascending and Descending out of the ever-popular LEGO toy bricks. Lipson’s explanation on his webpage should satisfy all but the most demanding LEGO-nerd. Descriptions of some of the pieces used to build the model as well as many photographs of the work-in-progress are provided and help explain just how Lipson and Shiu achieved the illusion.

Many other people have built and photographed their own impossible Staircases; and, while true Penrose Staircases cannot function in the real world, we see that three-dimensional representations can be tricked into being.

And, of course, through clever camerawork Christopher Nolan is able to put a Penrose Staircase on the big screen. The illusion appears twice in the film, actually, but the second time is probably overlooked even more often then when it is first explained. Near the end of the film, as Arthur is being pursued through a stairwell, a quick change of angle points the camera straight downward. Our hero is supposed to be further down the stairs than his chaser, but suddenly he descends another flight of stairs and catches up to the bad guy from behind. The stunned villain is caught off guard and thrown off the front of an abruptly ending staircase. The impossibility of it all can only be realized in the paradoxical world of the movie’s dreams. And it is this manipulation of reality that compliments an intelligent script and encourages filmgoers to view the film over and over, seeing if there is anything they might have missed the first time around (or second, or third…).

No comments:

Post a Comment